Welcome and introduction of Dr Liz Craig.

No mai, haere mai:

Dr Craig, Members of Parliament, colleagues, health sector professionals, patients and carers – a very warm welcome to you all.

I’m Ken Romeril, of Myeloma NZ, and I’m delighted to see this wonderful turn out this morning.

It’s particularly pleasing to see such a strong turnout of patients from around the country. Because you are at the centre of today’s purpose, which is to chart the way forward in the treatment of myeloma, and in doing so, to improve your quality of life and survival, and that of patients in future.

We are honoured to have this meeting hosted by Dr Liz Craig.

Dr Craig entered Parliament at the 2017 election following a significant career as a public health doctor, in particular making her mark in researching, monitoring and advocating for the health of NZ’s children and young people.

We applaud you for deciding to enter politics. May I say it’s great to have a doctor in the House. But it really is great to have someone of your calibre and your medical background in the Parliament, to bring your experience to bear on health policy-making, and we wish you the very best in your political career.

Dr Craig will shortly formally launch our burden of disease report – the Burden of Multiple Myeloma: A study of the Human and Economic Costs of Myeloma in New Zealand.

As most people in this room know, myeloma is a blood cancer that resides in the bone marrow. It is a horrible, incurable disease that affects multiple sites in the body, and follows an unpredictable, remitting, relapsing course with often increasingly serious complications. Being diagnosed with myeloma generally turns people’s lives upside down.

We will hear today – and you will find in these reports – accounts from patients of the impact this disease has on their lives and those of their families. We thank all of you who’ve contributed their stories and took part in our survey.

It’s a unique study, with the main report accompanied by a separate summary The Way Forward, and an overview of the survey’s findings, Patients’ Perspectives. We hope that together these will serve as a platform for further research and initiatives for improving outcomes.

The report has been a long time in gestation, but we think the wait has been well worthwhile, and we’re looking forward to sharing its findings with you in the presentations ahead.

But for now, it’s my real pleasure to invite Dr Craig to welcome you to Parliament and – although we don’t have a bottle of bubbly to break on its bow – we invite you to formally launch our report. Dr Liz Craig.

Key Treatment Priorities

Hello again.

As Richard has explained, this report drills deeply into the complicated condition that is multiple myeloma.

We commissioned it because there was a dearth of information on its incidence, prevalence and impact on the lives of a significant number of New Zealanders.

I’m going to briefly run through its key conclusions and recommendations.

One of the first things that became obvious was that the NZ Cancer Registry only records patients at diagnosis and death, and there is no clinical information about staging, cytogenetic data and treatment.

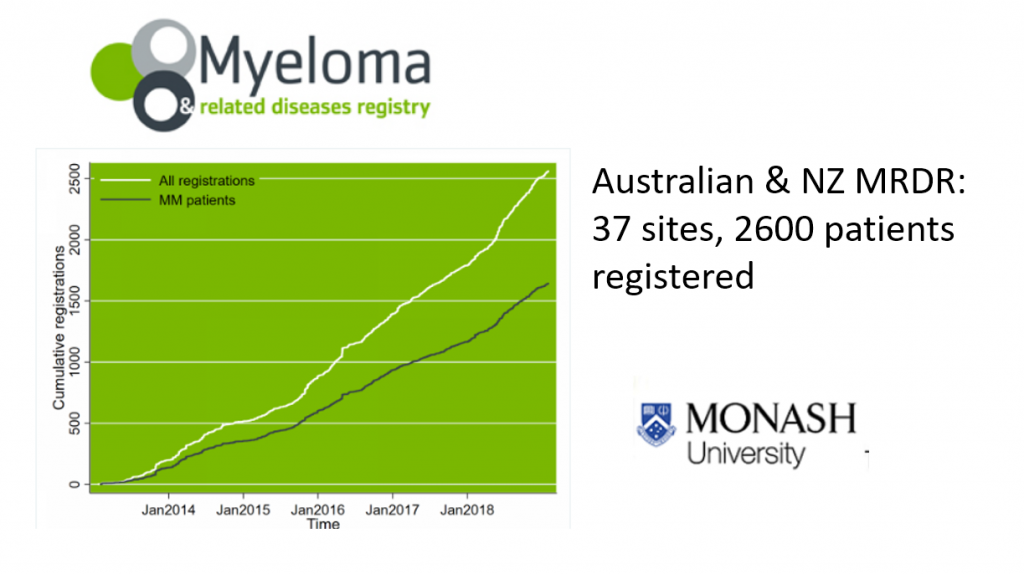

The good news is that we’re now able to participate in the Myeloma & Related Diseases Registry established at Monash University in Melbourne in 2012.

This is an excellent tool that collects data on patterns of treatment and variations in patient outcomes – both survival and quality of life – and is already producing data and articles for publication. It’s now set to expand into the Asia Pacific area.

We’d like to see all NZ centres to participate in this registry because we can extract the New Zealand data and, ultimately, evaluate the translation of advances in therapy into long terms outcomes.

So we’ll be able see how we’re performing outside the setting of clinical trials. And we can accurately compare ourselves to Australia, and the wider Asia-Pacific area as they come on board.

Among the issues for action here is a need for funding for centres to employ data administrators, as often clinicians and nurses don’t have the time to do this.

Survival is no doubt the issue of most intense interest to us all. I’ve seen a steady improvement in survival over the last 40 years in my work as a haematologist, largely due to improved clinical management and the availability of new treatments.

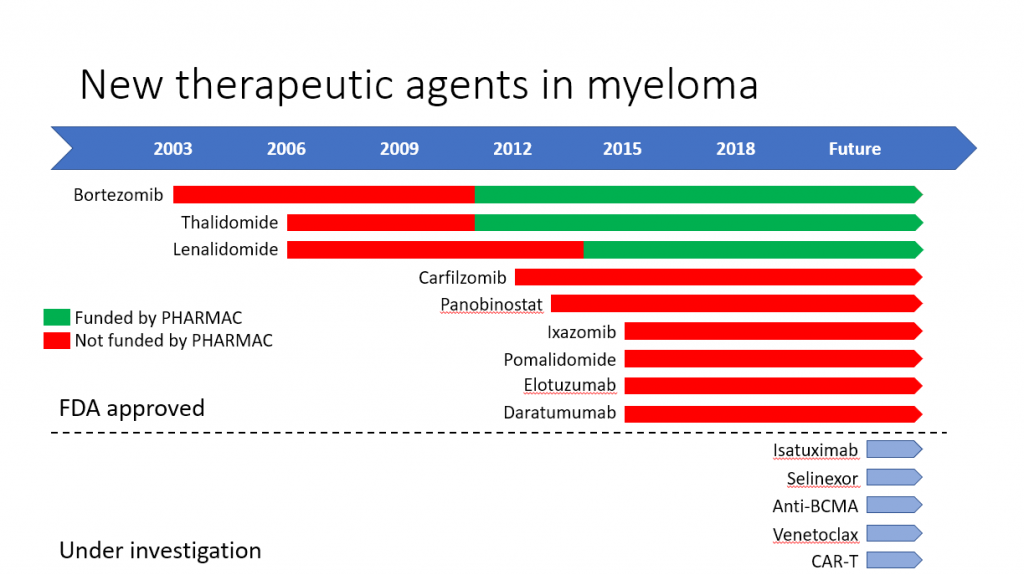

In the last 20 years, since we’ve been able to use thalidomide from the year 2000 and more recently bortezomib and lenalidomide, there have been very significant gains in survival.

We have now achieved 5 year OS rates of around 44% and are able to tell new patients that they can hope for survivals of 7 to 10 years. There will always be outliers who survive for much longer – my star patient David Nicholson – where are you David? – has the record of 21 years since his myeloma diagnosis.

And unfortunately there will also always be a small group that do not reach the average survival, and this is an unmet clinical need.

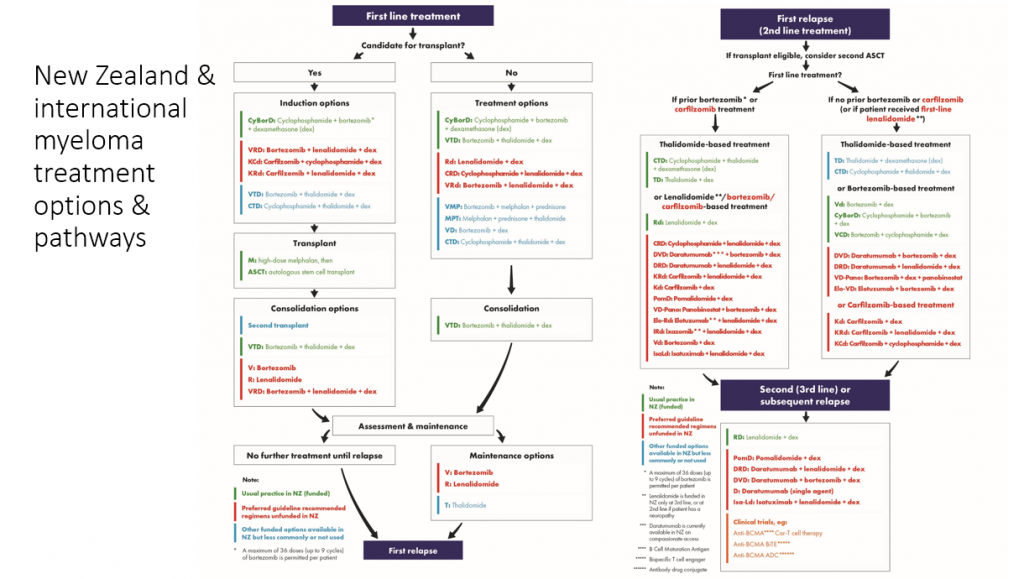

The great promise represented by these newer medications – you can see in the sea of red in this slide – combined with their huge costs is a major issue that all countries are grappling with.

And this gives you an idea of the range of novel treatments available but not yet funded here.

This is an important message from this report:

We know there are no easy answers, but we do know that some countries have come up with solutions: models for providing rapid access to some of these new medications, which for some patients can mean the difference between life and death.

Some of these models include sharing the risk and cost with pharmaceutical companies who make these drugs, and we are asking the government to look at these models and move urgently on this. It is one of the hardest things for clinicians to know that there are treatments out there that could transform a patient’s life, but we can’t provide them to our patients.

The patient survey that we undertook as part of this study made it clear that patients would like clinicians and organisations such as Myeloma NZ to advocate with the government for new treatments. While we have no intention of being unruly or unprofessional, we are doing – and must do – our best in this regard, including by

• working constructively through the normal channels with Pharmac,

• petitioning Parliament on behalf of patients, as we recently did,

• and – just last week in fact – making a submission to the Health Select Committee.

We invite all of you to weigh in constructively on this issue. We want you to feel empowered to do so. David Simpson will talk further abut these issues.

What we also know is that a number of patients are taking matters into their own hands and have organised self-importing of generic drugs. The issue here

is that this may bypass the pharmaco vigilance schemes that the companies have set up to ensure patient safety.

Another important consideration is the array of the new management strategies on the horizon. I encourage you to read the opening section of the Way Forward on the recent advances in the field of myeloma management.

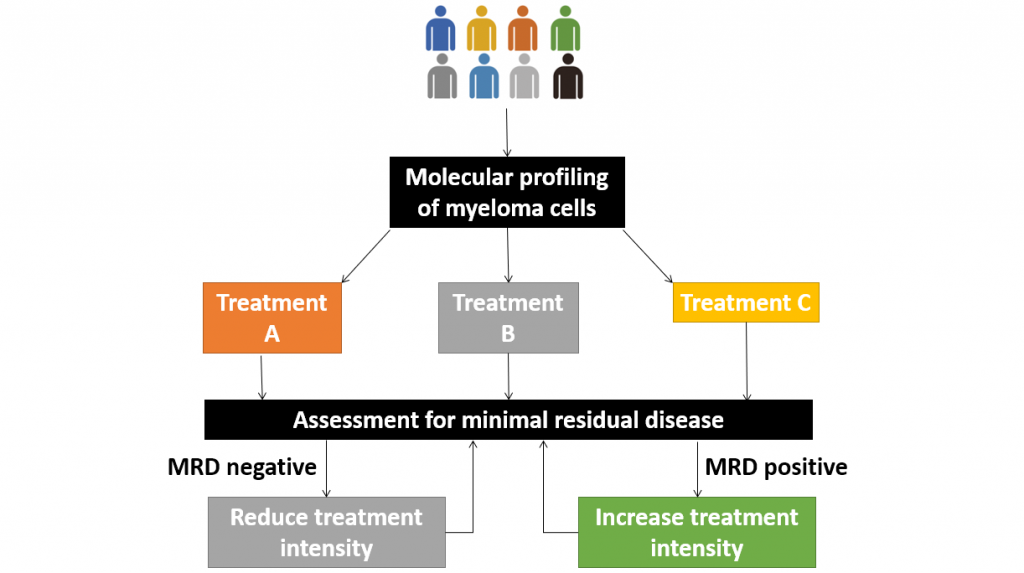

Molecular profiling – that is the analysis of DNA mutations within myeloma cells – is likely to help us optimise and improve treatment in future and will likely be more economical than FISH studies.

There are other promising developments in this area that may pave the way for a more tailored and targeted treatment strategy and away from the approach of giving the same treatment to everyone.

Minimal Residual Disease analysis is also proving valuable in management. Some of the novel treatments are now achieving a depth of response that is beyond the sensitivity of traditional tests.

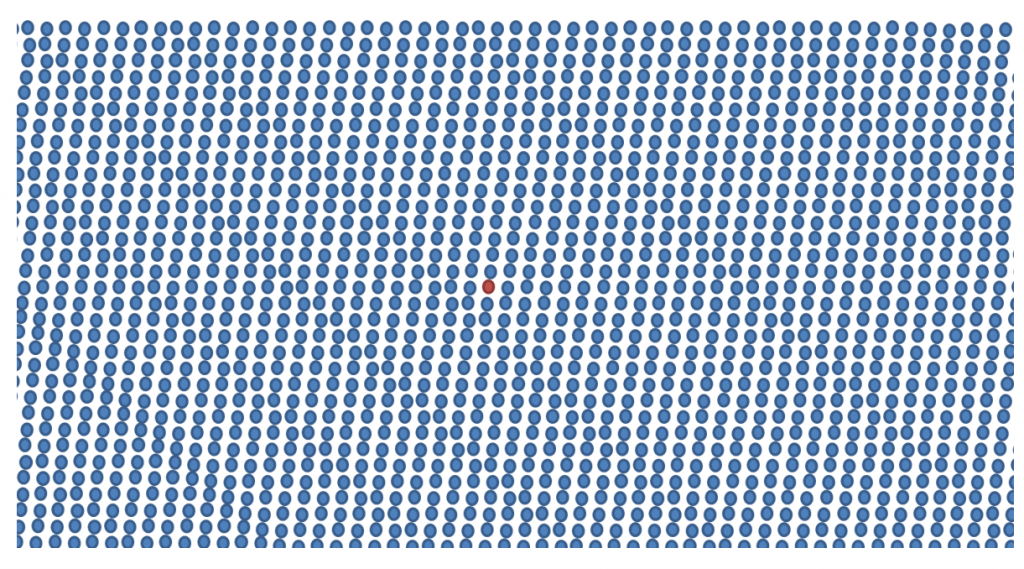

Current technology allows scientists to detect 1 myeloma cell among a sea 100,000 to 1 million cells. A bit like Where’s Wally

This raises the possibility of having a response-adapted treatment plan, based on MRD results.

Patients who are MRD negative can forgo further treatment, while those failed to achieve MRD negativity may receive intensification of treatment.

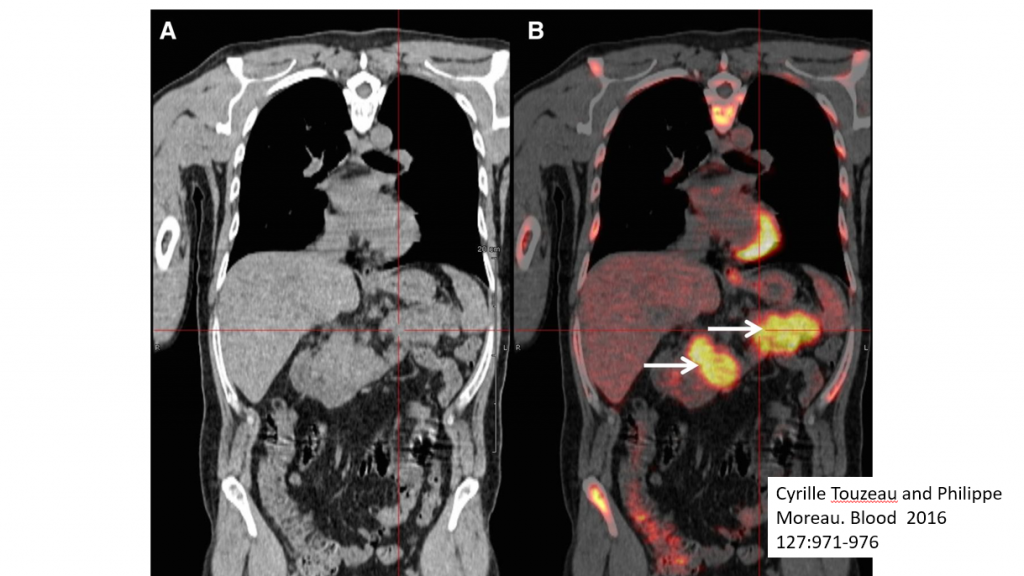

Many other aspects of myeloma management have already undergone significant change. Plain x rays no longer cut the mustard and so the role of low dose CT, MRI and eventually PET scans will be an integral part of the staging.

In this slide image A is from a CT scan showing the presence of myeloma, and B is from a PET scan that better highlights the same lesions – shown by the arrows.

Among important findings to come out of the patient survey was that there was often a significant delay in diagnosis. As an example of this, I recently saw a patient who’d had back pain for a year and felt no-one was listening. He had to insist on an MRI which showed myeloma deposits in his spine. Clearly much more education is required to raise awareness of how myeloma may present.

Patients are also calling for better, clearer information about their disease and its treatment. We hope that the three publications we are launching today will be a good start on that.

An important recommendation arising from the report is the need to improve equity of access to treatment, and also how to improve delivery to the rural areas that are some distance from the main centres. It doesn’t make sense to be travelling once a week on a 3 hour return trip to get a 5 minute subcutaneous injection of Velcade.

Initiatives such as district nurse administration, closer partnering with general practice and providing equipment for patients to be able self-administer at home should be considered.

I want to turn to the finding of regional variations in outcomes which was high-lighted in this report. There is a strong suggestion that patients living on the North Shore fare better than patients living in rural areas and even in some areas of the North Island close to main centres. We need to understand what lies behind this and see how we can best deliver the optimal, best-managed practice to all regions.

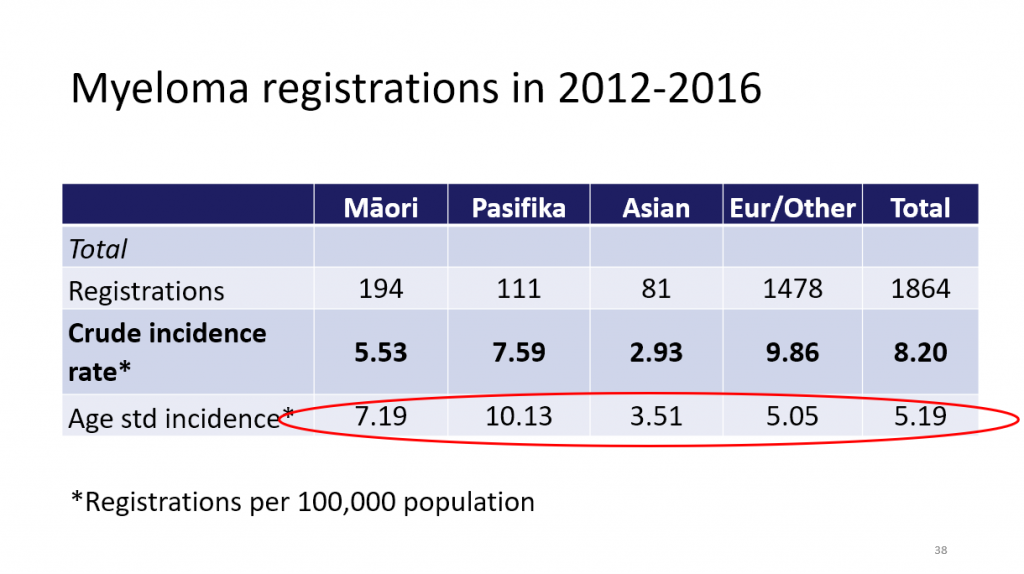

There was a higher age-standardised rate of myeloma in Māori and Pasifika people. Here’s the slide that Richard showed you.

Māori and Pasifika are also younger at diagnosis, have lower uptake of stem cell transplant, and for younger Māori and Pasifika, survival is poorer.

There is also poorer survival and lower uptake of stem cell transplant for people living in the most socio-economically deprived areas. These are all concerning factors that call for further research.

Finally, we know that patients who receive a stem cell transplant have better survival and so the finding that the uptake in the 65 – 69 age group is quite low is another matter of real concern. This can depend on fitness for transplant, but more research needs to be done in this area to work out why these people are not getting to transplant. In the US, for example, we know that stem cell transplant is considered for patients up to the age of 75, depending on fitness.

In summary, the report has highlighted a number of important issues that we can work on collaboratively.

As I trust is clear from our approach today and the way we have framed our reports, our message is one of hope:

• we can and must take advantage of the new diagnostic techniques and treatments now available to us, and the new data and information that we now have before us.

• We are confident that working purposefully and collaboratively we can turn these recommendations into action.

• In so doing, we will steadily move towards the day where myeloma patients are living well, with a good quality of life, and an illness that can be managed as a chronic one, rather than a fatal one.

Thank you.